Indonesia’s Corruption Eradication Commission deputy chairman Laode Muhammad Syarif, is sounding a warning about the bad side of Chinese investments beyond its borders—the potential for corruption and economic influence. China’s investments in Southeast Asia and Africa nations have a good side and a bad side. The bad side of Chinese investments is about corruption and economic influence.

“We are advising the government to be more careful with investment from China .They are doing it as a part of their business, trying to expand their economic influence, so that’s why we have to be very, very careful.”

He points to studies by corruption watchdog agencies like Global Corruption Watch, which found that that Chinese-supported projects consistently resulted in a rise in local corruption through bribes and other mediums, and worse development outcomes, compared to projects supported by other countries.

Alarm about the corruption that follows Chinese investments in Africa. He makes references to a 2017 survey of Chinese firms operating in Africa, which found that 87% admitted to paying bribes to local officials.

“That and other analysis concludes that Chinese business norms do not find corruption objectionable,” he says. “Reinforcing that, although the Chinese government has a crackdown on corruption inside China, it has paid little attention to corruption by Chinese businesses and state-linked firms outside the country.”

Kenya and Uganda are two good cases in point. “The Kenyan and Ugandan governments are currently investigating nearly 1,000 separate cases of tax evasion and related bribery by Chinese or Chinese linked companies in those countries.

Corruption from China is the last thing Southeast and African nations need. They already have plenty of it, according to Transparency International rankings. And it has been one of the killers of whatever economic progress these nations have made in the past.

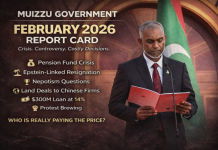

But there’s more about the bad side of Chinese investments: Many of these projects aren’t economically viable; they are built to be inflated; and leave the host countries heavily indebted to China, as has been the case with Sri Lanka and Djibouti, which end up ceding control of their ports to Beijing.

That’s how Chinese investments end up being agents of Beijing’s economic influence in the Southeast Asia and Africa.